|

| America's Historical Newspapers, Library of Congress |

John Pierpont Morgan was a legendary American financier and banker who dominated corporate finance on Wall Street throughout the 'Gilded Age' in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century's. As the head of the banking firm that ultimately became known as J.P. Morgan and Co., he was a driving force behind the wave of industrial consolidation in the United States spanning the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Morgan was also one of the greatest art and book collectors of his day, appropriating treasures from across the globe and he donated many works of art to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

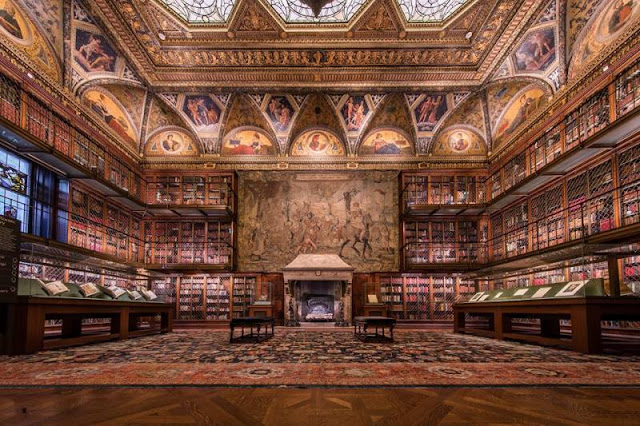

By the time he entered his early 60s his collection had already expanded beyond what his various homes could hold, so in 1902 he commissioned the construction of a library to house is impressive collection of rare books on Madison Avenue, New York.

|

| The Morgan Library and Museum |

Morgan knew he needed someone to manage and grow his literary collections, his nephew Junius served in an advisory capacity at Princeton University Library where a young clerk named Belle da Costa Greene had greatly impressed him with her lustrous passion for books and keen mind and intellect. So in 1905, on his nephews recommendation he hired Bella for $75 dollars a month (up from $40 at Princeton).

|

| Bella da Costa Greene |

Soon trusted for her expertise (Greene was an expert in illuminated manuscripts) as well as her bargaining prowess with dealers, Greene would handle millions of dollars buying and selling rare manuscripts, books and art for Morgan. The power that she wielded for forty-three years, first as librarian, and then as the first director of the Morgan Library, was unmatched. She told Morgan – who was willing to pay any price for important works – that her goal was to make his library "pre-eminent, especially for incunabula, manuscripts, bindings, and the classics." She believed the British Museum and the Bibliothèque Nationale to be their only real rivals.

Greene has been described as smart and outspoken as well as beautiful and sensual. While she enjoyed a Bohemian freedom, she was also able to move with ease in elite society, known for her exotic looks and designer wardrobe. "Just because I am a librarian," Greene reportedly announced, "doesn't mean I have to dress like one." She wore jewels and gowns to work and when in Paris she stayed at the Ritz. Not only did her bearing, style, and seemingly unlimited means attract notice, but her role at the Morgan Library placed her at the center of the art trade and her friendship was coveted by every dealer.

|

| Pastel Portrait, 1913 |

She always claimed her middle name and striking looks came from her paternal Portugese grandmother, Genevieve de Costa Van Viliet, but nearly all the information she gave out regarding her background in her lifetime, was completely false. Forty years after the end of the Civil War, she had some persuasive motives for obscuring the true facts of her origins. Her given name was not Belle da Costa Greene but Belle Marton Greener, and she was the daughter of the first African-American man to graduate from Harvard.

Her mother was Genevieve Ida Fleet, a member of a well-known African-American family in the nation's capital, while her father was Richard Theodore Greener, an attorney who served as dean of the Howard University School of Law and was the first black student and first black graduate of Harvard (class of 1870). After his separation from his wife (they never divorced), Greener became a U.S. diplomat posted to Siberia, where he had a second family with a Japanese woman. Once Greene took the job with Morgan, she likely never spoke to her father again. After her parents' separation, the light-skinned Belle, her mother, and her siblings passed as white and changed their surname to Greene to distance themselves from their father. Her mother changed her maiden name to Van Vliet, apparently in an effort to assume Dutch ancestry, while Belle dropped her given middle name, Marion, for "da Costa" and began claiming a Portuguese background to explain her complexion.

She defied every stereotype associated with her occupation. Although notoriously promiscuous, she was hard working and extremely talented. Her formidable proprietor trusted her skills unreservedly and she added many fine treasures to Morgan's collection. According to Heidi Ardizzone, who teaches American studies at the University of Notre Dame, Greene wanted above all to make “the rare books she prized so highly available to the public, not locked in the vaults of private collectors” — and eventually she met this goal. In 1924, when Morgan’s library became a public institution and Greene was named its first director, she celebrated by mounting a series of exhibitions, one of which drew “a record 170,000 people.”

When he died in 1913 J. P. Morgan left Greene $50,000 (equivalent to $1,300,000 in 2021) in his will. Asked if she was Morgan's mistress, Greene is said to have replied, "We tried!" Once, she recalled, Morgan asked if she might love him "if he were thirty years younger. I said no, I’d leave the library – he would be too dangerous – which seemed to please him. And then he said he never wanted to be younger except when he was with me and thought of me. I don’t doubt he has said that to every woman he knows but I love him just the same."

Greene retired from the Morgan Library in 1948 and died in New York City two years later, leaving a lasting legacy of collections, contributions to scholarship, mentoring future generations and widely promoting and championing the work of illustrious female scholars and librarians.

Post a Comment